I am constantly thinking about what it means to be a person online these days—the act of using computers to find, discover, share, and engage with each other about information. For people like me, computers and social technologies are part of an evolutionary tradition of humans making experiences more pleasant and productive by building and iterating on tools for humans to use.

Those of us who have been growing up alongside the internet may recall a phenomenological period of time colloquially known as Eternal September—when the internet shifted from being a place where tinkerers and computer nerds like me dominated discussion boards (called usergroups, newsgroups, and bulletin boards back then) to a place where anyone and everyone became a potential customer to a massive explosion in online commercialization experiments that internet historians and nostalgic older investors refer to as the Dot-Com Bubble.

For over two decades, I've observed a fundamental tension in the internet's evolution: the dialectic between those driven to create tools for utility and human connection, and those seeking to extract commercial value. While these aims aren't mutually exclusive—after all, commercial ventures must provide utility to survive—this tension shapes how we build and interact with digital spaces. A common attitude among programmers is that solving one's own problems likely solves others' problems as well, exemplified in the radical yet deeply human endeavor of open source development. We are, when you really take away everything else, creatures that have evolved by means of using and in order to use tools.

Tools and tool-building also includes blueprints for building tools—like protocols that help developers write predictable and uniform ways of sending and receiving information across networks. In the social technology space, BlueSky has emerged as an interesting juxtaposition of a centralized topic (commercialization in social spaces) implemented in a decentralized way. Despite my hesitations around venture capital and blockchain—especially when the two concepts are intertwined like they are with BlueSky's latest investors—the humans on the technology team consistently display a reasoned and welcoming approach to thinking about these problems in a way that motivates people to not only get involved, but also adopt the mindset of what is readily apparent as a precondition for working at BlueSky: being pioneers.

Pioneering is something that we don't get to see much of these days. Commercial interests in online spaces have dwarfed most efforts of exploratory computing, the niche communities in between systems that everyone uses everyday and theoretical things that could improve existing systems or re-imagine existing ways of implementing and using systems. These communities exist (I always joke: "there are dozens of us!"), but as my own joke surreptitiously highlights, I'm not sure if they/we are just hard to find or if we are just so few and far between...

What really blows my mind is that for all that the internet and computing has become, we are still very young in our joint evolution alongside computer technology. To put it into perspective, consider this: I'll be 40 years old in two years, and right now there's active research into quantum computing as a means of breaking some of the strongest cryptographic techniques that we are able to implement. We have people champing at the bit for artificial general intelligence, and already machines that can mimic intelligence in the way that an adolescent can mimic adult-like behaviors. Contrast all this to just one generation ago, my parents' generation, when as children they learned about giant magnetic tapes that could be moved from machine to machine, and punch cards you could feed into a machine that performed algebra like magic.

We have come a long way, and we are still just beginning our ascent into whatever cybernetically enhanced future we will undoubtedly find ourselves in. That's both exciting as well as deeply unsettling, as our evolving relationship with computing tends to center around our ability to capture potential revenue. But scientific and technological achievements must not become vectors for equivalently sophisticated means of exploitation, lest we find ourselves in a paradox where our higher-purpose intellectual pursuits in evolving our understanding of and relationship to computers exacerbates the way in which other humans can exploit us with them.

This is why communication technology has always interested me so much. Social technology, social media, messaging, chat, message boards, forums... We have opportunities that were not available to the generations before us: to connect with one another and share information artifacts in a virtual instant—and in doing so, enabling novel ways of mediating our social construction of reality. But these tools of connection present us with a dialectic between their emancipatory potential and their capacity for social fragmentation.

Older than computing is our relationship to storytelling, and one of the stories in the zeitgeist reminds us that with great power comes great responsibility. When storytelling and computing collide, we can have great things like CMSs and blogs and ebooks. But we can also have not-great things, like disinformation, election interference, and whole political parties that emotionally manipulate and psychologically exploit parts of our brains that evolved for a pre-technological world. To approach stories we find and share online with the essential criticality of a reality-constructing participant in a reality-constructing social enterprise is less a function of opportunity these days and instead a function of economic and educational privilege. Those of us who might not feel like pioneers but nevertheless engage in pioneering work must therefore ensure that the tools we build serve not just commercial interests, but also the broader project of technologically-mediated reality construction.

Around the Net

- Mike Masnick uses Threads as an example of how moderation in online spaces is not something that can be done without knowledge and inclusion of context:

I’ve talked in the past about the importance of understanding context, and how many content moderation failures are due to the lack of context. But it seems difficult to see how the largest social media company on the planet wouldn’t have tools in place that let you look at “I stand by my views of Hitler. Not a good guy” and think you don’t have the context to realize that post is probably not hate speech.

That said, some of this may also come down to the constant drumbeat and criticism of Meta over its moderation choices in the past. There’s a reason why the company has increasingly said that it doesn’t want to be a platform for discussing politics or the latest news (and actively downranks such content in its algorithms).

But also, come on. These kinds of mistakes are the sorts of things you’d expect to see in a brand new startup run by two dudes in a coffee shop, who hacked together some free-off-GitHub code to handle moderation. Not a company worth $1.5 trillion.

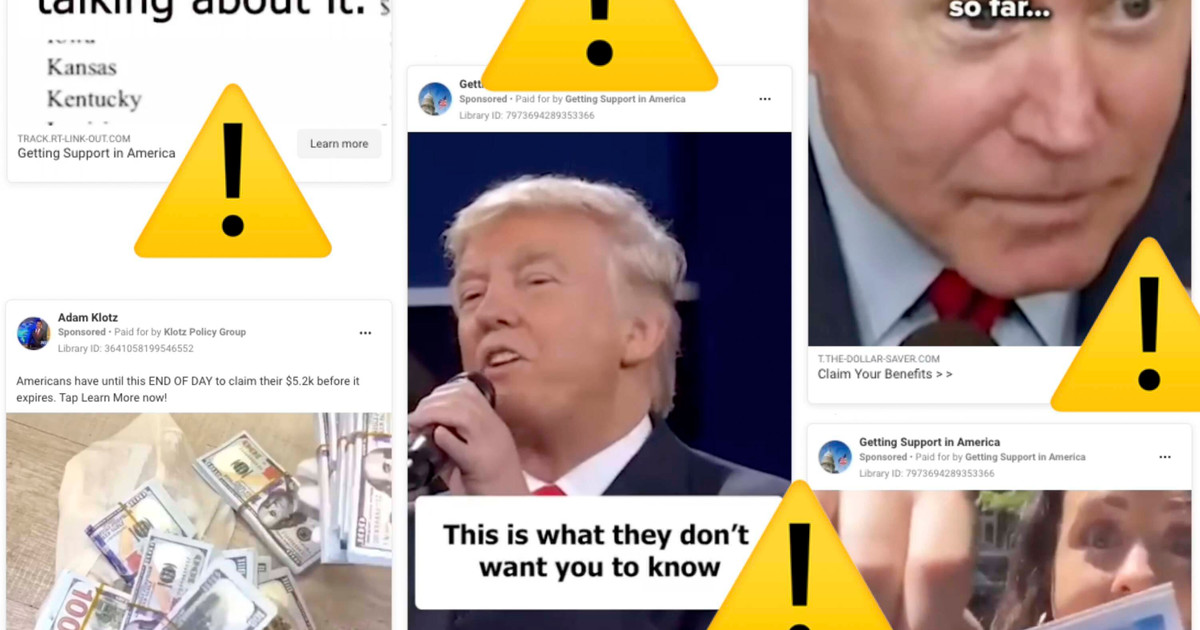

- Lulu Ramadan's investigation into political ads on Meta platforms reveals a dark network of disinformation amplifiers seeking to scam people out of money. Interestingly, Meta earns about $115,000,000,000/year just in advertising revenue—and when you discovery why entities are paying Meta so much, it becomes apparent that it's a small overhead compared to the sheer volume of illicit revenue they can generate:

Most of these networks are run by lead-generation companies, which gather and sell people’s personal information. People who clicked on some of these ads were unwittingly signed up for monthly credit card charges, among many other schemes. Some, for example, were conned by an unscrupulous insurance agent into changing their Affordable Care Act health plans. While the agent earns a commission, the people who are scammed can lose their health insurance or face unexpected tax bills because of the switch.

- Joyce Arthur's The Only Moral Abortion is My Abortion is both a prescient topic for today's election as well as a must-read for anyone and everyone for whom reproductive rights are a priority:

“My first encounter with this phenomenon came when I was doing a 2-week follow-up at a family planning clinic. The woman’s anti-choice values spoke indirectly through her expression and body language. She told me that she had been offended by the other women in the abortion clinic waiting room because they were using abortion as a form of birth control, but her condom had broken so she had no choice! I had real difficulty not pointing out that she did have a choice, and she had made it! Just like the other women in the waiting room.”

This issue of Weekender, along with everything else I've worked on this week, would not be possible without you. I left my corporate job at the beginning of October 2024 to focus on my work—video essays on TikTok, written essays here on my blog, and open-source development of social technologies. Your continued financial support enables me to continue on.

—Jesse